The Prevention of Corruption Act is a key Indian law made to stop bribery and protect honest officials. It sets clear rules for public servants and punishes corrupt ones. The Prevention of Corruption Act was first passed in 1988. Later, it was changed with the Prevention of Corruption (Amendment) Act, 2018. This law talks about many crimes like bribery, undue advantage, and criminal misconduct.

One important part is section 7A of Prevention of Corruption Act Amendment 2018. It explains how a public servant who takes a bribe can be punished. The section 7A of Prevention of Corruption Act also speaks about the need for prior approval before prosecuting. The section 7 PC Act punishment is strict. Section 13 of Prevention of Corruption Act deals with criminal misconduct too. The Prevention of Corruption Act helps make the government clean and fair.

Significant Amendments in the Prevention of Corruption Act, 2018

The Prevention of Corruption Act, 2018 brought major reforms. It introduced Section 7A for punishing bribe-givers, redefined criminal misconduct, and added Section 17A requiring prior approval before investigating public servants. These changes aim to balance protection for honest officials with stricter punishment for corruption and promote ethical governance.

Section 7: Offences Relating to Public Servants, 2018

Section 7 of the Prevention of Corruption Act, 2018 punishes public servants who accept or try to accept undue advantage for doing official work. It aims to stop bribery and ensure clean administration. The section includes strict jail terms and fines to promote honesty and integrity in public service.

Section 7A: Influencing Public Servants

Section 7A of the Prevention of Corruption Act punishes anyone who offers a bribe to influence a public servant. Even if the bribe is not accepted, the act is punishable. This section was added in the 2018 amendment to target those who attempt to corrupt officials performing public duties.

Section 8: Bribing Public Servants

Section 8 of the Prevention of Corruption Act punishes people who give or promise to give undue advantage to public servants. It holds individuals accountable even if they act through intermediaries. This aims to discourage bribery from both sides and maintain transparency in public dealings.

Section 9: Commercial Organizations and Corruption

Section 9 of the Prevention of Corruption Act targets companies and commercial organizations involved in bribery. If any person associated with a company gives a bribe for business advantage, the company is liable. This section promotes corporate compliance and ethical business conduct in line with global standards.

Section 10: Liability of Persons in Charge of Commercial Organizations

Section 10 of the Prevention of Corruption Act holds directors, managers, and secretaries responsible if their organization is found guilty under Section 9. If they failed to prevent bribery or were involved, they face punishment. This promotes accountability and corporate responsibility in preventing corrupt practices.

Section 11: Undue Advantage to Public Servants

Section 11 of the Prevention of Corruption Act punishes public servants who accept anything of value without a lawful reason. Even if there’s no direct favor promised, accepting gifts or benefits is illegal. This section helps stop indirect forms of corruption and promotes ethical behavior.

Section 12: Abetment of Offences

Section 12 of the Prevention of Corruption Act punishes anyone who abets an offence under the Act. Whether the offence is committed or not, helping or encouraging corruption is a crime. This ensures that all parties involved in corrupt activities are held accountable.

Section 13: Criminal Misconduct by Public Servants

Section 13 of the Prevention of Corruption deals with criminal misconduct by public servants. It includes dishonest use of power, misappropriation, and possession of disproportionate assets. This section ensures strict punishment for corrupt officials who misuse their position for personal benefit or cause loss to the government.

Section 17A: Prior Sanction for Prosecution

Section 17A of the Prevention of Corruption requires prior approval from the Central or State Government before investigating public servants. It protects honest officials from harassment. This provision balances the need for accountability with safeguards against frivolous or politically motivated investigations.

Key Features of Section 17A:

- Mandatory Prior Approval Section 17A requires prior approval from the Central or State Government before initiating any investigation against a public servant. This protects officials from harassment and ensures that only serious and well-examined cases proceed, promoting fair treatment while maintaining accountability for genuine acts of corruption.

- Applies to All Public Servants The provision covers all public servants, including high-ranking officers. Whether in the Central or State Government, no investigation can begin without the required sanction. This universal application ensures consistent protection across all levels of administration and prevents selective targeting or politically motivated actions.

- Focus on Official Acts Section 17A applies only when the alleged offence relates to decisions or actions taken while performing official duties. It ensures that genuine administrative decisions, made in good faith, aren’t criminalized unnecessarily, thereby protecting honest governance and encouraging efficient public service without fear.

- No Sanction Needed for Traps While prior approval is required for investigation, it is not needed when a public servant is caught red-handed in a trap case (like accepting a bribe). This allows anti-corruption agencies to act quickly in clear cases of wrongdoing without waiting for permission.

- Prevents Frivolous Investigations One of the main goals of Section 17A is to stop baseless or politically driven cases. It filters out weak complaints before an investigation begins, ensuring that only credible allegations are pursued, thus safeguarding reputations and maintaining the integrity of public service.

- Balancing Act Between Protection and EnforcementSection 17A strikes a balance,it protects honest officials while still allowing investigations into real corruption with proper approval. It reflects a legal shift toward structured accountability, aiming to reduce misuse of power without weakening the overall fight against corruption under the Prevention of Corruption.

Impact of the Repeal of Section 13(1)(d)

The repeal of Section 13(1)(d) of the Prevention of Corruption removed the broad definition of criminal misconduct. Earlier, it punished public servants for causing undue gain without proof of bribery. Its removal reduced misuse and protected honest decision-making but raised concerns about weakening anti-corruption enforcement in complex cases.

- Mandatory Prior Approval for Investigation: Section 17A introduced the need for prior sanction before investigating a public servant. This aims to protect honest officers from harassment over routine decisions. However, critics believe it may slow down urgent investigations and give corrupt officials a shield against swift legal action.

- Bribe Givers Also Held Accountable: Section 7A punishes not only public officials who accept bribes but also those who offer them. This provision reflects a significant shift in the Prevention of Corruption, targeting both sides of a corrupt transaction and promoting responsibility among private individuals and organizations.

- Corporate Entities Can Be Prosecuted: Section 9 extends liability to commercial organizations whose employees or agents offer bribes. This forces companies to maintain strong anti-corruption practices. While it raises corporate accountability, it also increases legal risks for businesses operating in complex or high-pressure public sector environments.

- Repeal of Section 13(1)(d): The repeal narrowed the definition of criminal misconduct. Earlier, officials could be charged for any decision that indirectly benefited someone. Now, the focus is on tangible offences like misappropriation or illicit wealth. While clearer, it may allow some corrupt practices to slip through legal gaps.

- Traps Allowed Without Sanction: Though Section 17A mandates prior approval for investigations, it makes an exception for trap cases,like catching someone accepting a bribe. This allows anti-corruption officers to act immediately in clear cases. It balances legal protection with the need for real-time enforcement.

- Greater Protection for Honest Officials: The amendments aim to protect public servants acting in good faith. By tightening investigative procedures, the law reduces fear among officials who take bold decisions. However, this protection must be monitored to ensure it doesn’t become a loophole for the corrupt.

- Increased Emphasis on Compliance: The Prevention of Corruption now demands commercial organizations to develop internal compliance systems. This includes staff training, anti-bribery policies, and regular audits. It encourages ethical business, though smaller firms may struggle with the cost and complexity of implementing such controls.

- Alignment with Global Norms: Recent changes in the Act bring it closer to international standards like those outlined by the UN Convention Against Corruption. By focusing on transparency, accountability, and legal safeguards, India signals a move toward cleaner governance and improved investor confidence in public systems.

Landmark Judgments on the Prevention of Corruption Act

Several Supreme Court cases have shaped the interpretation of the Prevention of Corruption . In the State of Maharashtra vs. Dr. Budhikota Subbarao (1993), the Court stressed the need for sanction before prosecution. Vineet Narain vs. Union of India (1996) led to stronger CBI autonomy and monitoring. Subramanian Swamy vs.

State of Maharashtra vs. Dr. Budhikota Subbarao (1993)

In this case, the Supreme Court ruled that no court can take action against a public servant under the Prevention of Corruption without prior sanction. The judgment reinforced the legal safeguard meant to protect honest public officials from unnecessary or politically motivated prosecutions.

Vineet Narain vs. Union of India (1996)

This landmark case led to major reforms in India’s anti-corruption framework. The Supreme Court directed greater independence for the CBI and set guidelines for transparent investigation. It boosted accountability and strengthened the implementation of the Prevention of Corruption across all levels of governance.

Subramanian Swamy vs. Manmohan Singh (2012)

In this case, the Supreme Court held that delays in granting sanction for prosecution under the Prevention of Corruption violate the rule of law. The Court emphasized that competent authorities must decide requests for sanction within a reasonable time to ensure timely action against corruption.

Lalita Kumari vs. Government of Uttar Pradesh (2014)

The Supreme Court ruled that filing an FIR is mandatory for all cognizable offences, including those under the Prevention of Corruption. This judgment strengthened the first step in anti-corruption investigations and ensured that authorities cannot delay or deny registration of valid complaints.

Implications for Public Servants and Commercial Organizations

The Prevention of Corruption places strong responsibilities on both public servants and commercial organizations. Public servants face strict punishment for bribery, criminal misconduct, and holding disproportionate assets. Sections like 7, 13, and 17A ensure accountability while offering protection through prior sanction rules.

For Public Servants

- Emphasis on Prior Approval: Section 17A of the Prevention of Corruption requires prior sanction before starting any investigation against a public servant. This protects honest officials from harassment but may also delay action against corruption, making it harder for investigating agencies to respond quickly to serious and time-sensitive complaints.

- Clear Liability for Bribe-Givers: Section 7A punishes anyone offering a bribe to influence a public servant, whether or not the bribe is accepted. This provision targets corruption at its root, creating fear for those who try to corrupt government systems, and complements efforts to hold bribe-takers equally accountable.

- Corporate Accountability Strengthened: Section 9 places liability on commercial organizations when anyone associated with them offers bribes for business benefits. This pushes companies to adopt strict anti-corruption policies, train employees, and ensure ethical conduct, aligning private sector behavior with the goals of the Prevention of Corruption.

- Focused Definition of Misconduct: The removal of Section 13(1)(d) narrowed what qualifies as criminal misconduct. Now, the Prevention of Corruption targets clear acts like illicit enrichment or misuse of funds, rather than broad interpretations. This helps prevent misuse of the law but might weaken action against subtle corruption.

- Balanced Protection and Enforcement: The amended Prevention of Corruption tries to strike a balance between punishing corrupt officials and protecting honest ones. By requiring prior approval for investigation and tightening definitions, it seeks to prevent abuse of power while ensuring accountability and fairness in the legal process.

- Shift Toward Global Standards: The changes in the Prevention of Corruption bring Indian law closer to international anti-corruption norms. It encourages ethical governance, transparency, and clean business practices. These reforms help build public trust and support India’s efforts to create a corruption-free administrative and corporate environment.

For Commercial Organizations

- Tighter Rules for Public Servants

The amended Prevention of Corruption holds public servants strictly liable for bribery and misappropriation. With defined offences like undue advantage and criminal misconduct, the law ensures accountability while aiming to protect honest officials through required prior sanction before investigation under Section 17A. - Section 7A Adds Bribe Giver Liability

Section 7A of the Prevention of Corruption Amendment 2018 punishes anyone attempting to influence a public servant through bribes. Even if the bribe isn’t accepted, the act is punishable, making the bribe giver equally responsible and targeting corruption from both the giver and receiver sides. - Greater Protection for Honest Officers

Section 17A mandates prior approval before starting any investigation, preventing misuse of the law. This protects honest public servants from false or political cases, encouraging fearless decision-making while maintaining strict action against genuine offenders through legal and structured prosecution processes. - Corporate Corruption Addressed

Section 9 makes companies and commercial organizations accountable if their agents bribe public officials. Businesses now need strong internal anti-corruption measures, ethics policies, and training to comply with the law and avoid legal penalties, supporting cleaner business practices in line with global anti-corruption efforts. - Repeal of Section 13(1)(d) Narrows Misconduct

With the removal of Section 13(1)(d), the law now focuses on specific misconduct like illicit enrichment or asset misuse. This removes vague interpretations and helps avoid misuse, though critics argue it may limit action against complex corruption not covered by narrow definitions. - Modernized Legal Framework

The Prevention of Corruption amendments bring India closer to international anti-corruption frameworks. These reforms aim to improve transparency, reduce frivolous prosecutions, and build public trust in governance by clearly defining offences, enhancing corporate liability, and strengthening legal protections for upright public servants.

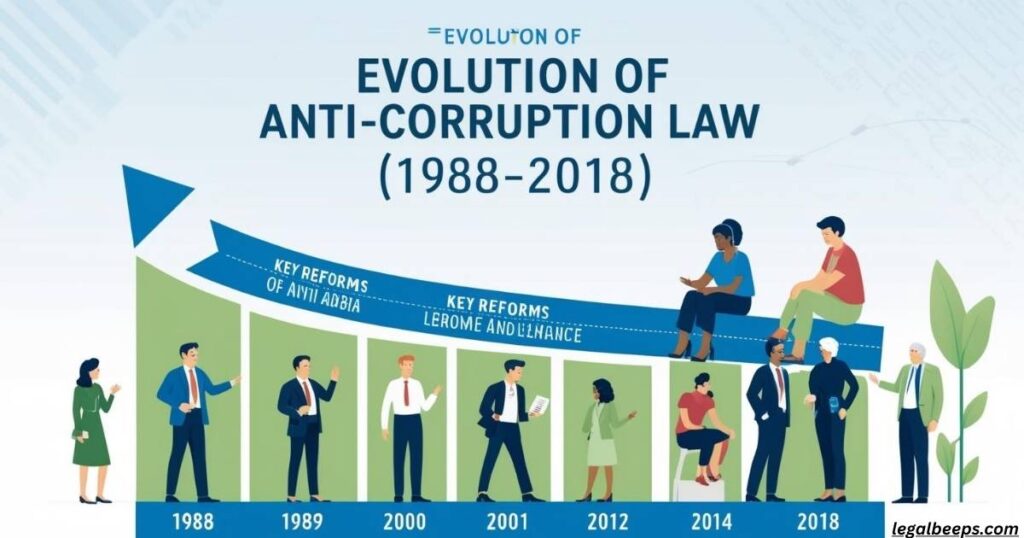

Evolution of Anti-Corruption Law from 1988 to 2018 Reforms

The Prevention of Corruption, 1988 marked a major step in India’s legal fight against corruption. It defined offences like bribery, criminal misconduct, and abuse of official position. Public servants could be prosecuted for holding disproportionate assets or causing unlawful gain. However, the law was often criticized for being too broad and vague.

Over time, cases like Vineet Narain vs. Union of India (1996) and Subramanian Swamy vs. Manmohan Singh (2012) exposed weaknesses in the legal process. Investigations were slow, and sanction for prosecution was often misused to delay justice. There was growing demand for better protection of honest officials and stricter penalties for corrupt ones.

In response, the Prevention of Corruption (Amendment) Act, 2018 brought major reforms. It introduced Section 17A for prior approval before investigation and focused misconduct definitions. The reforms emphasized corporate liability, ethical governance, and aligning Indian law with global anti-corruption standards.

Comparative Analysis of Indian and Global Anti-Corruption Frameworks

India’s anti-corruption laws, especially the Prevention of Corruption, have evolved to meet growing demands for transparency. The 2018 amendments brought in stricter definitions, corporate liability, and the need for prior sanction under Section 17A, offering legal protection to honest public servants. However, enforcement still faces challenges like delays, political interference, and low conviction rates.

Globally, frameworks like the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention and the UN Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC) promote stricter compliance, independent oversight, and whistleblower protection. Countries like the United Kingdom have laws such as the Bribery Act 2010, which imposes strict corporate liability and requires businesses to prove adequate preventive procedures,a more proactive stance compared to India’s reactive approach.

While India has taken major steps to align with international norms, global systems often stress preventive measures, transparency mechanisms, and swift prosecution. To match this, India needs stronger implementation, judicial speed, and consistent anti-corruption policy enforcement.

Judicial Interpretation of Safeguards for Public Servants

Indian courts have played a crucial role in interpreting safeguards for public servants under the Prevention of Corruption. A major example is the requirement of prior sanction before prosecuting officials, which courts have upheld to protect honest decision-making and prevent frivolous or politically motivated legal action.

In Subramanian Swamy vs. Manmohan Singh (2012), the Supreme Court emphasized that delays in granting sanction for prosecution undermine the rule of law. The court ruled that sanctions must be given within a reasonable time to avoid shielding corrupt officials while still protecting the innocent.

The introduction of Section 17A in the 2018 amendment reinforced this safeguard by mandating prior approval before investigation. However, courts continue to balance this protection with the need for accountability. Judicial interpretations stress that these safeguards must not become a barrier to justice but must ensure fairness in corruption investigations.

Read Also: Latest Visa Rejection Reasons & How Legal Experts Can Help

Transparency and Governance Challenges under Section 17A

Section 17A of the Prevention of Corruption was introduced to shield honest public servants from baseless probes. While it aims to prevent harassment and ensure fair governance, it has also sparked debate about transparency and accountability in the investigation process.

One major concern is that mandatory prior approval from the Central or State Government can delay or even block investigations, especially against powerful officials. This can weaken public trust in anti-corruption efforts and create space for corrupt practices to go unchecked under bureaucratic protection.

Furthermore, Section 17A may discourage whistleblowers and investigating agencies, who fear that necessary approvals will not be granted. Critics argue that while protecting integrity in governance is vital, there must be clear timelines, independent scrutiny, and safeguards to ensure Section 17A doesn’t become a tool to hide corruption instead of curbing it.

Legislative Intent Behind the 2018 Amendments to the Prevention of Corruption Act

The 2018 amendments to the Prevention of Corruption were designed to modernize India’s anti-corruption law and align it with global standards like the UNCAC. The key intent was to create a more balanced legal framework that punishes corruption effectively while protecting honest public servants.

One major objective was to introduce clarity in defining offences. The repeal of Section 13(1)(d) narrowed the scope of criminal misconduct, focusing now on direct acts like misappropriation, illicit enrichment, and bribery. This move aimed to prevent the misuse of vague legal terms against officials acting in good faith.

Another core aim was to hold commercial organizations accountable through Section 9, encouraging stronger internal compliance systems. The introduction of Section 17A, requiring prior approval before investigation, was meant to curb frivolous probes. Overall, the amendments sought to ensure ethical governance, legal precision, and fair prosecution.

FAQ’s

What is Section 13 of the Prevention of Corruption Act?

Section 13 of the Prevention of Corruption deals with criminal misconduct by public servants. It punishes misuse of position, bribery, and illegal personal gains.

What is Section 17A of the Prevention of Corruption Act?

Section 17A of the Prevention of Corruption requires permission from the government before starting any investigation against public servants for official decisions.

What is criminal misconduct under the Prevention of Corruption Act?

Criminal misconduct under the Prevention of Corruption includes misusing position, stealing public funds, or having assets beyond legal income limits.

What is abetment under the Prevention of Corruption Act?

Abetment under the Prevention of Corruption means helping or encouraging someone to commit bribery or any other corrupt act punishable under this law.

What is considered disproportionate assets under the Prevention of Corruption Act?

Disproportionate assets mean property or money owned by a public servant that is more than their legal income, as punished under the Prevention of Corruption.

Conclusion

The Prevention of Corruption Act plays a big role in fighting corruption in India. It targets bribery, misuse of power, and unfair gains. Section 7 PC Act punishment deals with taking money for doing or not doing official work. Section 13 of Prevention of Corruption punishes public servants for criminal misconduct and illegal wealth. The Prevention of Corruption helps protect public trust and improve honesty in government work.

Section 7A of Prevention of Corruption gives rules for when someone offers a bribe to help with public duties. Section 7A of Prevention of Corruption Amendment 2018 added stricter steps. Section 7A of Prevention of Corruption Amendment 2018 punishment includes jail and fines. The Prevention of Corruption supports clean governance. It sets rules for all public servants. The Prevention of Corruption Act is key to stopping corruption in India.